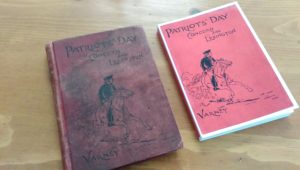

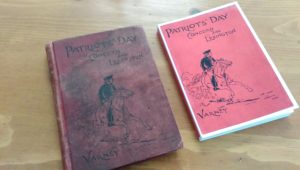

It’s with great pleasure that I announce that we at Battle Road Books have produced a replica of this wonderful little book: Patriots’ Day by George Varney

Our goal at Battle Road Books is to keep the history of the Revolutionary War alive and vibrant and easily accessible. We also don’t think you should pay an arm and a leg just to read these old books.

On the left is the original book. It’s a little book – I’m finding that many of the old books I’m buying are small – just a bit smaller than 5″x7″. On the right, of course, is the “reincarnation.” It is not a scanned copy – have you seen those? – they’re a mess. Nope. We lovingly went through every page of this book and made each page as close to the original as possible.

It is a book that was produced in 1895, written by George Varney, as a celebration of the 100th anniversary of the Battles of Lexington and Concord. I love this book and am thrilled that you’ll be able to love it too.

Here’s the Preface:

PREFACE

The bill abolishing the practice of appointing annually a day of ”fasting and prayer,” having passed the Massachusetts House of Representatives, received the approving vote of the Senate on March 16, 1894, and was on the same day signed by the governor, Frederic T. Greenhalge. The bill also established the nineteenth day of April as an annual holiday. The latter, therefore, is the legitimate successor of Fast Day, which had come to be observed chiefly by its desecration.

The first proclamation of the new holiday was issued on the eleventh day of April, 1894, and gave it, most appropriately, the name Patriots’ Day. Neither the statute nor the proclamation prescribed any definite form of celebration; consequently, there is ample scope and freedom for the preferences of communities and organizations in its observance. The proclamation was as follows: —

”By an act of the Legislature, duly approved, the nineteenth day of April has been made a legal holiday.

”This is a day rich with historical and significant events which are precious in the eyes of patriots. It may well be called Patriots’ Day. On this day, in 1775, at Lexington and Concord, was begun the great war of the Revolution; on this day, in 1783, just eight years afterwards, the cessation of war and the triumph of independence were formally proclaimed; and on this day, in 1861, the first blood was shed in the war for the Union.

”Thus the day is grand with the memories of the mighty struggles which in one instance brought liberty, and in the other union, to the country.

”It is fitting, therefore, that the day should be celebrated as the anniversary of the birth of Liberty and Union.

”Let this day be dedicated, then, to solemn religious and patriotic services, which may adequately express our deep sense of the trials and tribulations of the patriots of the earlier and of the latter days, and also especially our gratitude to Almighty God, who crowned the heroic struggles of the founders and preservers of our country with victory and peace.”

It is earnestly and devoutly to be desired that the sentiments of this proclamation shall imbue every breast; that patriotism shall more and more take the form of

religion, holding relation, not to one nation only, but to all the peoples of the earth; that the happy time may come when justice, forbearance, and magnanimity will so prevail among men that violent and destructive differences between individuals, communities, states, and nations will be prevented by wise tribunals chosen and empowered to adjudicate disputes and establish peace and amity in all lands.

For the incidents and data of this presentation of the opening conflict of our Revolutionary War, I am indebted in part to several works, a list of which may be found on the last page of this volume.

The illustrative views, except the view of Lexington Green, the two flags, and the diagrams of Concord and Lexington, are from photographs made since 1875; and most of the objects remain the same to the present date.

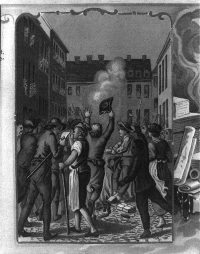

The view of the conflict at Lexington is from a copper-plate engraving made previous to December, 1775, and accurately represents the scene as preserved also by history and tradition. A room in the building at the left (Buckman’s Tavern) was used by John Hancock as an office while the Provincial Congress held its sessions in Concord. The large building in the middle is the first church, with the belfry on the ground nearby, as it stood at the time. Another illustration in the poems is from a recent photograph of the same belfry as it now appears.

It should be explained that the patriots’ guns were not pointed as shown in the picture until the British had opened fire. In the background appear the ranks of the main body of the ”Regulars” on the march towards Concord, nearly seven miles to the right of Lexington Green, or ”Common” as it has been called in recent years.

Boston, April 3, 1895.

Posts taken from this book:

The Scar of Lexington”

A Minuteman’s Story of the Concord Fight

Stories Heard on Father’s Lap

Stories Heard on Grandpa’s Lap

MacKenzie goes on, “If we had had time to set fire to those houses many Rebels must have perished in them, but as night drew on Lord Percy thought it best to continue the march.”

MacKenzie goes on, “If we had had time to set fire to those houses many Rebels must have perished in them, but as night drew on Lord Percy thought it best to continue the march.”

It is generally agreed that the stars on the 13 Star Flag were chosen to represent the 13 colonies and that the stars replaced the British Union. The Union was the familiar symbol of the British flag which represented a "union" of the Cross of St. George, the symbol of England, which was a red cross on a white background and the cross of St. Andrew, the symbol of Scotland, which was a diagonal white cross on a blue background. The Union flag was created when Scotland and England joined as one empire in 1707.

It is generally agreed that the stars on the 13 Star Flag were chosen to represent the 13 colonies and that the stars replaced the British Union. The Union was the familiar symbol of the British flag which represented a "union" of the Cross of St. George, the symbol of England, which was a red cross on a white background and the cross of St. Andrew, the symbol of Scotland, which was a diagonal white cross on a blue background. The Union flag was created when Scotland and England joined as one empire in 1707.

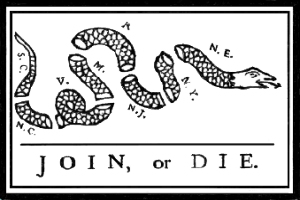

Colonial relations with Great Britain had been deteriorating gradually since the Stamp Act of 1765. The Tea Act of 1773 brought things to a head with a small tax placed on imported tea. Though the tax was small, the colonists were firm in their belief that Parliament did not have the right to tax them since they had no representation there. Instead, they believed the proper bodies to institute taxes on them were their own elected legislatures.

Colonial relations with Great Britain had been deteriorating gradually since the Stamp Act of 1765. The Tea Act of 1773 brought things to a head with a small tax placed on imported tea. Though the tax was small, the colonists were firm in their belief that Parliament did not have the right to tax them since they had no representation there. Instead, they believed the proper bodies to institute taxes on them were their own elected legislatures.

Parliament's response to all this preparation was to pass the New England Retraining Act, which was signed by the King on March 30, 1775. This Act forbade Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island and Connecticut from trading with any other countries but Great Britain or her colonies. The idea was to strangle the colonists into a position of desperation so they would drop their opposition and consent to Parliament's demands. The Acts also forbade them from using the North Atlantic fisheries off Nova Scotia and Newfoundland, a heavy blow to the colonists, who were dependent on the food and income from the fisheries.

Parliament's response to all this preparation was to pass the New England Retraining Act, which was signed by the King on March 30, 1775. This Act forbade Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island and Connecticut from trading with any other countries but Great Britain or her colonies. The idea was to strangle the colonists into a position of desperation so they would drop their opposition and consent to Parliament's demands. The Acts also forbade them from using the North Atlantic fisheries off Nova Scotia and Newfoundland, a heavy blow to the colonists, who were dependent on the food and income from the fisheries.

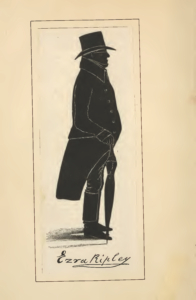

The next book I'm going to put out was written in 1827 and is titled History of the Fight at Concord, on the 19th of April, 1775 by Ezra Ripley.

The next book I'm going to put out was written in 1827 and is titled History of the Fight at Concord, on the 19th of April, 1775 by Ezra Ripley.

There are many versions of the story with a number of names for this equine hero. Among them, Sparky. That doesn’t sound very heroic. The Larkin family history says the horse was named Brown Beauty. Still, not all that heroic a name. Seems like it should have been William Wallace or something. But I digress.

There are many versions of the story with a number of names for this equine hero. Among them, Sparky. That doesn’t sound very heroic. The Larkin family history says the horse was named Brown Beauty. Still, not all that heroic a name. Seems like it should have been William Wallace or something. But I digress.