The Sons of Liberty Flag was originally flown in Boston by the Sons of Liberty, a loose knit association of colonists resisting British efforts to take away their liberties. The flag had 9 vertical red and white stripes. The flag became known as the "Rebellious Stripes" and was eventually outlawed by the British. The colonists reversed the stripes to horizontal and kept using it in protests against tyrannical attempts to tax them against their will. Eventually the stripes grew to 13, representing unified resistance from all 13 British colonies.

History of the Sons of Liberty Flag

The Sons of Liberty were formed in Boston around the time of the Stamp Act protests in 1765. Local patriots would meet at a large elm tree to protest. This became known as the Liberty Tree. They began to fly this flag whenever the leaders would want to call the townspeople together and it became known as the Sons of Liberty Flag or the Liberty Tree Flag. Legend says the 9 stripes represented the 9 colonies that attended the Stamp Act Congress to coordinate their dissent.

The Sons of Liberty were formed in Boston around the time of the Stamp Act protests in 1765. Local patriots would meet at a large elm tree to protest. This became known as the Liberty Tree. They began to fly this flag whenever the leaders would want to call the townspeople together and it became known as the Sons of Liberty Flag or the Liberty Tree Flag. Legend says the 9 stripes represented the 9 colonies that attended the Stamp Act Congress to coordinate their dissent.

The Liberty Tree became a popular meeting place for the Sons of Liberty to express their dissent. Unpopular officials were hung and burned in effigy from the tree. Colonists posted notices threatening citizens who cooperated with British taxation schemes. The British finally cut the tree down in an effort to stop the dissent. The colonists erected a pole in its place called the "Liberty Pole" and flew the Sons of Liberty Flag from it instead. The flag came to be known as the "Rebellious Stripes" and was outlawed by the British. The colonists simply reversed the stripes and kept using it.

As word spread about the Liberty Tree and Liberty Pole in Boston, similar Liberty Trees and Liberty Poles sprung up around the colonies as meeting places for resistance against the British. Sons of Liberty groups formed across the colonies as well. The Boston Sons of Liberty reached the height of their influence at the Boston Tea Party in 1773, when they threw tea from the British East India Company into the harbor to protest unlawful British taxes. By the time the Revolutionary War started in 1775, the stripes had grown to 13, representing the unified resistance of all 13 colonies. From around 1776 to 1800, the Sons of Liberty Flag was used as a United States merchant flag for merchant shipping, so is sometimes called the Colonial Merchant Ensign (an ensign is a flag).

Questions about the history of the Sons of Liberty Flag

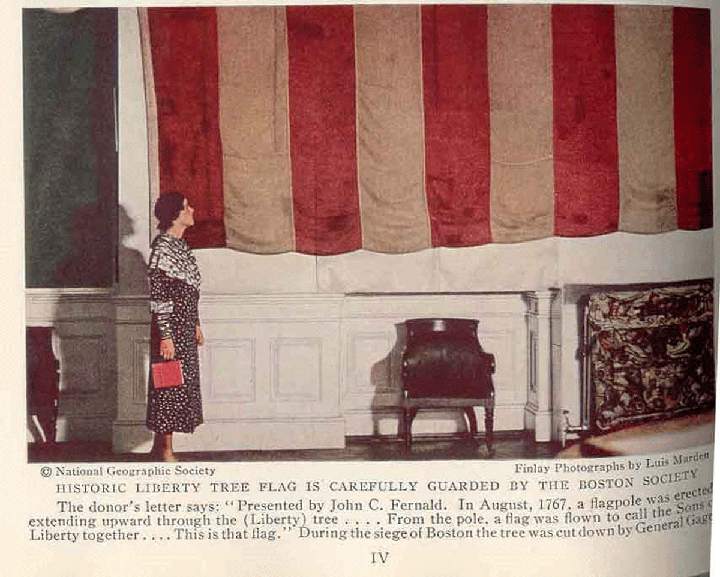

There are a few questions pointed out by historians about the traditional history of this flag. First of all, there is a very old Sons of Liberty Flag held by the Old State House in Boston that was featured in the July 1936 National Geographic Magazine. This flag was donated to the State House by a John C. Fernald in 1893. The year earlier he had loaned it to the Columbian Expedition in Chicago, which wrote this about the flag in its official catalogue of items:

Furnald told the State House he had purchased the flag from the grand-daughter of a wireworker named Samuel Adams who had died in 1855 at the age of 96. The idea that it had once flown from the Liberty Tree was passed on down through the family over the years. The problem is that this story cannot be verified from any other sources. It was purely a verbal tradition passed down in the family.

The story has several historical problems. First, the Liberty Tree was not on Boston Common, but a few blocks away. Second, there were likely no mass meetings of the Sons of Liberty at the tree in 1775 because there were so many British troops in the city. Third, Mr. Adams would have been 16 in 1775 and as a teenager would not likely have been given the responsibility of caring for the Sons of Liberty's flag, although it could have belonged to his father or grandfather before him.

The last problem is that modern historians have examined this Sons of Liberty Flag and believe it does not date from the Revolutionary War period due to its machine woven cotton cloth. Cotton cloth was not widely available until 1800 and machine woven cloth was very rare in 1775 as machine looms were very new at the time. Most cloth was still hand woven at this time.

Some historians believe this flag was not flown from the Liberty Tree at all, but instead, the flag flown was a British Red Ensign, the official flag of Great Britain and hence the official flag of the British colonies. Flying the British Red Ensign would have been illegal for colonists as the flag was reserved for military uses, but they may have flown it and added white stripes to symbolize their rebellion. This may have been the origin of the "rebellious stripes" label.

These historians point out that there are many contemporary references to the Boston patriots flying a flag from the Liberty Tree, but none of them describe the Sons of Liberty Flag with 9 red and white stripes. Instead, nearly all of those who describe the flag describe a red flag and call it a British or Union Flag (the Union representing the union of England and Scotland into Great Britain). If this is the case, as it appears to be, the Sons of Liberty Flag developed out of the British Red Ensign. Perhaps the colonists removed the British Union Jack from the corner of the flag as a gesture of defiance when the war began.

Sons of Liberty Flag in the Revolutionary War and Beyond

The Grand Union Flag, which was the first unofficial, though commonly used, flag of the united colonies, added 6 white stripes to a traditional British Red Ensign, the official flag of Great Britain. This may have been an effort to emulate the Sons of Liberty's "rebellious stripes."

The Sons of Liberty Flag may also be the basis from which the First Navy Jack Flag, the first US naval flag, was created, as well as the the first 13 star flag, the first official flag of the United States.

You may find a few variations of the Sons of Liberty Flag showing a snake, a cup of tea or other symbols in the center of the red and white stripes. These are not flags from the Revolutionary War era, but are modern variations of the flag. The only exception to this is the First Navy Jack Flag which has a snake over the words "Don't Tread On Me." This is traditionally considered to be the United States navy's first flag.

This article is a re-post from Revolutionary War and Beyond, our sister site.

Now certainly, Gage had been told in a letter from the Earl of Dartmouth, dated January 27, 1775, “It is the opinion of the King’s servants, in which His majesty concurs, that the first and essential step to be taken toward reestablishing Government, would be to arrest and imprison the principal actors and abettors of the Provincial Congress whose proceedings appear in every light to be acts of treason and rebellion.”

Now certainly, Gage had been told in a letter from the Earl of Dartmouth, dated January 27, 1775, “It is the opinion of the King’s servants, in which His majesty concurs, that the first and essential step to be taken toward reestablishing Government, would be to arrest and imprison the principal actors and abettors of the Provincial Congress whose proceedings appear in every light to be acts of treason and rebellion.”

Lord Hugh Percy was aristocracy. He was heir to a vast fortune, maybe the greatest in the western world at that time. He was a professional soldier from his teenage years and, when he came to America, was 32 years old.

Lord Hugh Percy was aristocracy. He was heir to a vast fortune, maybe the greatest in the western world at that time. He was a professional soldier from his teenage years and, when he came to America, was 32 years old.

. . . that it was flattened on one side by the ribs as if it had been beaten with a hammer. He was a plain, honest man, to appearance, who had voluntarily turned out with his musket at the alarm of danger, as did also some thousands besides, on that memorable day. [Doubtless Mr. Hemenway of Framingham.] In the same room lay mortally wounded a British officer, Lieutenant Hull, of a youthful, fair, and delicate countenance. He was of a respectable family of fortune in Scotland. Sitting on one feather-bed, he leaned on another, and was attempting to suck the juice of an orange which some neighbor had brought. The physician of the place had been to dress his wounds, and a woman was appointed to attend him.

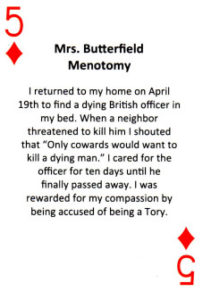

. . . that it was flattened on one side by the ribs as if it had been beaten with a hammer. He was a plain, honest man, to appearance, who had voluntarily turned out with his musket at the alarm of danger, as did also some thousands besides, on that memorable day. [Doubtless Mr. Hemenway of Framingham.] In the same room lay mortally wounded a British officer, Lieutenant Hull, of a youthful, fair, and delicate countenance. He was of a respectable family of fortune in Scotland. Sitting on one feather-bed, he leaned on another, and was attempting to suck the juice of an orange which some neighbor had brought. The physician of the place had been to dress his wounds, and a woman was appointed to attend him. As you may know, the worst of the fighting on April 19th, was in the towns of Menotomy (current day Arlington, MA) and Camden. Here is where we find Mrs. Butterfield.

As you may know, the worst of the fighting on April 19th, was in the towns of Menotomy (current day Arlington, MA) and Camden. Here is where we find Mrs. Butterfield.

The reactions of the King’s men were varied. Some were full of blame for their commanders. Others, who before this day started held the Americans in contempt, returned to Boston with grudging respect. The men who’d engaged these redcoats in battle were no longer thought of as mere farmers and merchants. They were soldiers.

The reactions of the King’s men were varied. Some were full of blame for their commanders. Others, who before this day started held the Americans in contempt, returned to Boston with grudging respect. The men who’d engaged these redcoats in battle were no longer thought of as mere farmers and merchants. They were soldiers.

* From The Story of Patriots Day by George Varney – Published by Lee and Shepard Publishers 1895. The reproduction of this wonderful little book is now available from Battle Road Books on

* From The Story of Patriots Day by George Varney – Published by Lee and Shepard Publishers 1895. The reproduction of this wonderful little book is now available from Battle Road Books on

“’We took the road for a while, and then left it and struck through the woods, a shorter cut to Concord. We passed Barrett’s mill before coming to old North Bridge. How indignant we were when we first caught sight of Captain Parsons’s detachment of British troops, with axes, breaking up the gun-carriages, and bringing out hay and wood, and setting fire to them in the yard.

“’We took the road for a while, and then left it and struck through the woods, a shorter cut to Concord. We passed Barrett’s mill before coming to old North Bridge. How indignant we were when we first caught sight of Captain Parsons’s detachment of British troops, with axes, breaking up the gun-carriages, and bringing out hay and wood, and setting fire to them in the yard.